Column 303 : In Defense of MicrosoftBy Jerry Pournelle October 17, 2005

The Grand Challenge Is Over!

Last year no one won the DARPA Grand Challenge, which was a 131 mile desert tour for autonomous—not teleoperated like Battlebots—vehicles. The race was declared a failure. It was a failure only if you think of the first Atlas launches as failures. This year five teams crossed the finish line, four in less than ten hours. The Stanford team won, but more importantly, DARPA declared victory. Mission accomplished.

This is a wonderful example of how government can help technology development. It's also an important development in robotics. Read about it at

http://www.grandchallenge.org/.

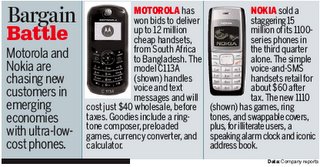

A montage of items reviewed this month.

The Times They Are A-Changing

Moore's Law was only an empirical generalization, but it contained a great truth: computing power grows exponentially, with a doubling time short compared to the span of a human generation. Every couple of years, limits to what computers can do come crashing down. Software inefficiencies become trivial. File sizes grow, memory requirements grow, and it scarcely matters. Slow and clunky programs run at acceptable speeds.

Sometimes we notice the improvements, sometimes we don't, but things just get easier and easier. When computer speeds are fast enough to make emulation penalties bearable, or even trivial, it may not matter at all what operating system you use or what chips your computer uses. That day may come sooner than you think.

Meanwhile, there's high pressure on all of us to change, upgrade, buy new software, lest the established companies go out of business. Microsoft searches for the Holy Grail: bug free systems easily upgraded, with compelling new features every year or two, all in color for a dime, or at least a few sawbucks.

Linux, meanwhile, hasn't got close to its goal of a Penguin on every desk, much less in every home and classroom, but there is visible progress; and Apple, flush with cash from iPod sales, looks to be making a comeback into the main computing arena. The most probable fate for Apple is to become the BMW of the computer world, and if I had to that's the way I'd bet it; but if Microsoft stumbles hard, Apple is still there to take advantage.

The future of Linux is murky. On the one hand the State of Massachusetts is mandating "open standards," particularly for public documents. This is widely seen as a move toward making Massachusetts "Microsoft Free," although a few think it a devious move in the complex legal chess game: Massachusetts is the last holdout in the Microsoft anti-trust suit.

Some go much further. Robert Bruce Thompson, a long time friend whose views I always take seriously, says "OpenOffice.org or, more precisely, the Open Document Format (ODF) that it uses, is the biggest threat that Microsoft has ever faced. Bigger than Linux and much bigger than Google. Massachusetts recently mandated that the executive department of their state government could use only open formats. This is catastrophic for Microsoft. Losing 60,000 desktops isn't even the big deal. The problem is that many other state and local governments may jump on the Massachusetts bandwagon, at a stroke eliminating Microsoft's Office format lock-in."

So far no other states have, and in fact there are counter-trends. One large hospital in Oregon, owned by savvy physicians with a lot of experience in IT, having experimented for several years with Linux servers is dumping them in favor of Microsoft 2003 Server because the costs of maintenance and support for the Linux boxes is just too high. A long time ago I pointed out that whatever else UNIX is, it's a full employment act for UNIX gurus. Apparently Linux is moving in that direction as well.

I know a lot of people with strong and fixed opinions about the future of Microsoft in the home, business, and government software markets, but not many of them agree with each other. Me, I think predictions at this point are about as accurate as reading tea leaves. If forced to give an opinion I'll bet on Bill Gates. He has a pretty good track record.

What's Next At Chaos Manor?

Even if you never stray from 100 percent Microsoft all the time, there are mighty changes in your future. I'd hoped to tell you about some of them, now that we have a newer beta of Microsoft Vista, but then we discovered that this particular beta has disabled many of the graphics features we'd hoped to investigate, and I think I'll leave Vista for another time. I do note that when you go to Control Panel Home, by default it is in category view. Go to Accessibility and you will find "Optimize for Blindness." We're just a bit afraid to click that button. It's still beta.

I have both Apple and Linux enthusiasts among my friends and advisors. They all keep telling me that if I'd just spend a week exclusively with my Mac, and another with a good system running Xandros Linux, I'd learn to get past the minor glitches and problems I find when I try to use those systems. I'd become trilingual, and then I would learn to love them.

They may be right. I certainly have writer friends who have long been "Microsoft free." Tom Clancy has always used a Mac. A couple of years ago I told you how Joel Rosenberg converted his whole household to Linux, although he did have to keep a Windows system going because his daughters were involved with games that would only play on a Windows system. Bob Thompson uses Linux exclusively except when he wants to run astronomy programs that only work on Windows. It's certainly possible to abandon Microsoft and survive.

I haven't done that, in part because I have no strong incentive to do so. Despite all the dire warnings, I haven't had a serious security problem since the Melissa virus a decade ago. I got seriously angry with Outlook last month, but I've solved that problem, as you'll learn in a bit.

For the most part, I'm happy with Windows, and I love TabletPC with OneNote.

In other words, I have no great reason to change operating systems, and I do much of my work in Microsoft Office. Office 2003 works for me. I like Word 2003 just fine, and in fact I depend on some of its features such as automatic correction of mistypings I commonly make. I like the built in thesaurus and access to dictionaries. I use FrontPage to keep my website going, and while I am no fan of elaborate presentations, I do find that I can use PowerPoint to organize simple outline charts to enhance my speeches. I gave several talks with PowerPoint at the recent North American Science Fiction Convention in Seattle, and they seemed to go over well; and I am now in the process of getting my old "Survival With Style" lecture which exists only on 35-mm. slides converted to some format PowerPoint can use.

On the other hand, I am sensitive to the "You don't know what you're missing" argument, and this month I did spend considerable time working with Ariadne the 15-inch PowerBook, doing some work that was far more conveniently done on a Mac than on a PC. More on that below, but my Mac enthusiast readers will be pleased to know that I got to the point where I was no longer frustrated by the Mac system, and there's a lot about it I like.

Is It War?

Recently there was a spate of articles about the Time of Troubles at Microsoft. According to many sources, in July 2004 Jim Allchin, a computer scientist by background, told Bill Gates that it just wasn't possible to make Longhorn work using the old Microsoft work system. Microsoft traditionally hires really bright people and turns them loose on problems they find interesting. They produce code that does cool things. It's then up to management to stitch all that stuff into one big system.

In the past this produced appealing but inelegant software. It was generally too large—"bloatware" has been a common term—and the first releases weren't very fast, but Moore's Law moves inexorably: what was too big and too slow last year is acceptably fast and not very large this year. I can recall my first 5 MB hard drive, a Honeywell Bull unit for the Lilith: it was as large as a 2-drawer file cabinet and the lights dimmed when we turned it on. Now I have a Kingston U3 Data Traveler that holds a gigabyte and it's not much larger than my finger. What was bloatware in the past is lost in the hardware of today and tomorrow.

The Microsoft coding system produced some pretty good stuff. It had lots of bugs, but there were lots of engineers to find patches for those bugs. After a while the code base was as much kludged as crafted, but the inexorable march of technology kept it going, until all those chickens came home to roost in 2004, culminating in the now famous Allchin report that Longhorn just wasn't going to work: they'd have to start over and work from a design. No more ad-lib coding by a bunch of uncontrolled geniuses.

This isn't the place to tell that story; my point here is that Microsoft has been trying to reinvent itself, and that hasn't been a smooth process. We still don't know how the story will turn out, but one thing is certain: the Microsoft near monopoly on operating systems for desktop computers is very much at risk.

Bill Gates knows this, but it's no surprise to him. He's always run scared, because he has always known that one consequence of Moore's Law is that any company that stands still will be obsolete in a rather short time. It really is a Red Queen's Race in which you have to run as fast as you can just to stand still; and Gates has always known that.

Now add to the mix the recent declaration of war by Sun's Scott McNealy and Google's Eric Schmidt. In a press conference October 5, McNealy and Schmidt rambled about how Microsoft has failed to exploit the Internet era, and is about to be left behind. While short on specifics, the new partners talked about Sun's OpenOffice program, which so far hasn't been much of a threat to Microsoft Office. With Google's talent and resources behind it, OpenOffice might actually become a rival to Office, and that will cut heavily into Microsoft's profits. And then there's the new network capability, and Google search engines, and network computing, and maybe there won't be any need for any stinking operating system, and there goes Windows.

To be fair, all of this was from Sun's Scott McNealy. Google said not one word about Microsoft or wars. Om Malik, Senior Writer for Business 2.0, told me he was disappointed. "Sun has become so irrelevant in the larger scheme of things that they needed the pizzazz from Google."

Some of us can remember this all happened before. Microsoft was slow at getting into the Internet and World Wide Web game, and Netscape came charging up. There were press conferences about the coming irrelevance of Microsoft, as network computing and "thin clients" would take over. Then, having declared war on Microsoft, the Netscape executives went about other business including sailboats. Perhaps they didn't take it seriously.

Now it's deja vu all over again.

Changing Times

Microsoft spokespeople made light of the whole thing. "What's to respond to? Where's the threat to us? We don't see the impact."

And perhaps they really see things that way in Microsoft management and over at the Waggoner-Edstrom Agency that so competently manages Microsoft public and press relations. But you can bet your back teeth there's one person at Microsoft who is taking the threat seriously, and that's Bill Gates. He at least knows that just because the "Network Computer" and thin clients weren't serious threats a decade ago, we're not living in the same technological world now. After all, Microsoft has been encouraging .NET for some time now, and some of us remember

Hailstorm.

And we all know that Google stole a march on Microsoft. The butterfly is straining mightily, but it's still playing catchup not only in search engines, but general web services. Remember those ads?

So. While it's silly to say that it's anybody's ball game—Microsoft has enormous advantages in this contest—it's no longer a fixed fight. For myself, I doubt that Network Computing will go much further this round than it did last time. I don't think I am alone in wanting control over my data and programs; in not wanting to be dependent on my net connections in order to function at all. Sometimes it's just smart to be paranoid.

Moreover, the same technology advances that make Network Computing possible also make your desktop computer more powerful. I am writing this on a machine that has more computing power than the entire ARPANET back in the early days, and my local network gives me enough local storage to hold multiple copies of everything I ever wrote, everything I ever read, and pretty near every picture I ever looked at. Sure the Internet is far more powerful, but as its power grows, so does my own, and as my personal computing power grows, the need for external resources diminishes.

The real war between Microsoft and Google is in competition for the best and brightest. Google is to today's Microsoft as Microsoft was to IBM in the late 1980's. Who wanted to work for IBM when they could go to the frontier, and maybe get rich from stock options?

Om Malik says "I think this isn't a war, it's a battle for the big brains. Microsoft was able to hire the smartest people in the world because it was seen as the company of the best and the brightest. Everyone wants to work with smart people. This isn't a war, and people are making far too much of this. It's a battle for talent and for future growth. Microsoft's profits aren't in danger."

Not now, at least; but Gates runs scared, and with good reason. The Microsoft image would change radically if the company became a Cash Cow, high profits and low growth, sort of like AT&T before Judge Green. Google is a rival, but for new business and growth potential, not for Microsoft's core business.

There's still room for growth out there, but not in Microsoft's traditional areas. Those are cash cows, and can't sustain exponential growth rates. Microsoft needs to look to other places. VOIP and the whole communications industry is changing. Gates tried a bold stroke in his satellite adventures with McCaw, but the timing was off, and they underestimated NASA's ability to sabotage private competition. One suspects that Gates hasn't forgotten that communications is still an international growth industry.

We can speculate all day, but it's still reading tea leaves. I will say this much: Microsoft may lose the upcoming wars, but if it does, it won't be to Sun and Network Computing.

Office 2003 SP-2

Your systems are all set to download and install Windows updates automatically, right? Good. If they're not, go do this NOW. The only reasonable exceptions would be if you're (a) in charge of testing compatibility with your (medium or large) company's software, or (b) if you don't have administrative access to your computer—in which case, call the guy from case "a."

Still: the Windows Update site doesn't update your Office applications, so it won't install Office 2003 Service Pack 2 (SP-2). If you don't have it, there's no reason not to go get it. Service Pack 2 includes systematic fixes for a bunch of bugs plastered over by earlier quick fixes, as well as incorporating a whole slew of security measures. The beta of Internet Explorer 7 supports "Microsoft Update," which offers updates to both Windows and Office applications, adding "Office Update" to "Windows Update". Very cool.

Office 2003 SP-2 also fixes some of my biggest complaints about Outlook 2003. Outlook is still a pig for resources, but it no longer claims over 90 percent of the system resources when downloading and processing incoming mail.

I've been running Office 2003 SP-2 since it came out, and I have had no problems with it. (Check

here to make sure your Office is up-to-date, whatever the version.)

The Horror

It didn't come in with Office SP-2, and I am not precisely sure when it did arrive, but they have "improved" Word to make it perhaps more useful, but at first sight less convenient. On the machine up in the Monk's Cell (once the room assigned to the oldest son still living in the house, now fitted out as a writing room with no games, no Internet connection, no telephone, and no books other than old high school textbooks and whatever research materials I have brought up for the current project), Word has simple one-click access to the internal Thesaurus and Dictionary. Of course Office hasn't been updated on that machine since I hauled it up there nearly a year ago.

None of the machines in the main office here have that capability. Instead, Help tells you that you must go to "Research" and there select what "research" you want: thesaurus, dictionary, encyclopedia. The default is "all research sites," and that leads you to some screwy place called High Beam Research, which appears to be a subsidiary of, or perhaps is owned by, Ask Jeeves. This all came about because I was writing a bit about iPod and the eponymous podcasts, and I wanted to be sure I was using the word "eponymous" properly. (It means "gave its name to," as in Lenin's eponymous city.) When I went to find the dictionary, though, I was conducted to High Beam Research (

http://www.highbeam.com/about/background.asp for more about them), and if you want to see horrors, go to Word, type in "eponymous," go to Tools, Research, and alt-click the word with the Research default set to "All Research Sites." You will be amazed.

However, there is a remedy. Do Tools, Research, and in the Search For list set it to "All Reference Books." That result is the one I expected. We haven't lost anything in the "improvement," but you do have to be careful what "research" you have set the system to do.

I suppose the "Research" tools have been in Office a long time and I just missed them. I also suppose that adding the online research, which for the moment is free but clearly is aimed at paid subscriptions, can make Office more useful.

Of course Office Help could have made that a bit more clear, but then no one expects Help to be very helpful. I did in fact figure it all out using several layers of Help, some patience, and a bit of help from Chaos Manor Associate Eric Pobirs who assured me that the dictionary and thesaurus were still in there, I only had to know how to find them.

Xerox DataGlyph Technology: Hide Data in Plain Sight

Xerox's PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) has been the wellspring for such technologies as the mouse, GUI computing, and the laserprinter. While not in that same honored pantheon, their DataGlyph technology is worth knowing about.

We ran into the technology while we were trying to serialize some paper documents—I won't say too much, but we'd want to know who leaked a copy, should it get out. Yes, we put in a plain-text serial number (a two-digit code in the lower right corner), but that's easily covered up. A 6-inch square watermark, though, is hard to cover up, short of retyping the entire 180-page document.

DataGlyphs are a way of embedding data into pictures and logos; you can find out about them at

http://www.parc.com/research/projects/dataglyphs/. In a DataGlyph, your data are expressed as tiny diagonal lines ("/" and "\"), essentially invisible except under great magnification; the image is assembled from the front- and back-slashes (which act, unsurprisingly, as zeroes and ones). The glyphs survive through most manipulations (changes of brightness, copying or faxing pages, etc), which interests Xerox's big-name partners who use the technology for serializing paper documents like insurance forms. Since we only needed two digits of data (the serial number), we opted for about 93 percent error-correction redundancy—more on that in a moment.

You can try out DataGlyphs yourself on the PARC

site, though you'll probably graduate quickly to the advanced interface. The advanced interface lets you upload your own graphic, choose the percentage of error-correction versus data carried, choose resolution from 200-1200 DPI, or play with other complex knobs and switches. Once you've created your glyph, you should upload it to the "Decode" engine on the same web page to make sure it actually decodes.

That quality-control step is necessary, lest you create write-only glyphs. We couldn't make glyphs decode if they had less than 5 percent minimum black in their dynamic range: even large white areas will have a little grey. The

glyph capacity spreadsheet helped us plan some of this, but it won't warn you about every bonehead setting you might try. Take notes, and vary from success rather than failure, if you're serious about trying the technology.

Be warned: in its current form, the Glyph-server is, as advertised, an experimental interface. It was fine for what we were doing, but it took a day to produce twelve glyphs and create .PDF print master documents. For our needs, targeted to printing on a Xerox Phaser 7700 laserprinter, the best settings seem to be 600 DPI, 20 pixel glyphs, 64 byte word size and 58 bytes of ECC.

As with many Xerox technologies, DataGlyphs haven't enjoyed the sort of success they probably deserved, and Xerox has made it pretty difficult to license a one-off copy of the software—they're concentrating on big corporate buyers. We'd probably pay money for a DataGlyph Office plug-in.

Making Your Mark

Glyphs also gave us a reason to try out Word 2003's watermarks, which have changed from previous versions. Now located in the Format -> Background -> Printed Watermark dialog box, watermarks can be text (diagonal or horizontal) or pictures. A light touch is best for watermarks, lest your text become illegible and your readers bring pitchforks and torches to your next meeting. There's a "Washout" feature, but for more accurate control, use PhotoShop or Paint Shop Pro and embed the final result at 100 percent size, with the brightness you like, rather than relying on Word's less precise controls.

Speaking of precision, Word 2003 only supports watermarks throughout the entire document, or not at all. Previous versions of Word support watermarks through the header/footer controls, through which you can delete the watermark in particular document sections. There should be a way to change or turn watermarks off by section in Word 2003, but neither Google nor I can find one.

We actually used Word 2000 to turn the watermark on and off as needed; alternatively, we were going to create an Adobe Acrobat PDF of the serialized pages, then replace the unserialized pages in a master Acrobat document. Be warned: creating an Acrobat file with an embedded 6-inch square 600 DPI watermark takes about 15 seconds per page on a 2 GHz AMD system.

Orchids and Onions

Nominations for the Chaos Manor annual Orchids and Onions Parade are now open. Please send your recommendations to

http://www.byte.com/documents/s=9502/byt1129581630969/mailto:usercolumn@jerrypournelle.com with the word "Orchid" or the word "Onion" as the subject. If possible, please use a separate message for each recommendation, and in particular please don't combine orchids and onions in the same message. If you wish your recommendation to be anonymous please say so. Messages become the property of J. E. Pournelle and Associates and may be published with or without attribution. Requests for anonymity will be honored. Give the name of the product, company, or individual, and if possible a link to where more information can be found, and state at reasonable length your reasons for wishing orchids or onions to the nominee.

All nominations will be considered, but no individual acknowledgment or response is guaranteed.

The annual Chaos Manor Orchids and Onions Parade has been a regular feature of the Chaos Manor column, and has appeared with the User's Choice Awards in BYTE since 1981. The 2005 results will be in the January, 2006 column.

Jerry Pournelle, Ph.D., is a science fiction writer and BYTE.com's senior contributing editor. Contact him at

http://www.byte.com/documents/s=9502/byt1129581630969/mailto:jerryp@jerrypournelle.com. Visit Jerry's Chaos Manor at

http://www.jerrypournelle.com/. Reader letters can be found at Jerry's

letters page.

For more of Jerry's columns, visit Byte.com's

Chaos Manor Index page.

Contact BYTE.com at

http://www.byte.com/feedback/feedback.html.