E, ano ngayon kung 1100 ang cellphone ko?!

Blogger's Note: I have a Nokia 1100 phone since I lost my 3510 unit. It is no match to my lost cellphone but it is cheaper and readily available. Others may have 3530, 6600, 8800, 9500 but I will still with my 1100. It is practical and less noticeable for pickpockets. Read this article with regards to regular cell phones. Read on... 8-)

NOVEMBER 7, 2005

EUROPEAN BUSINESS

Cell Phones For The People

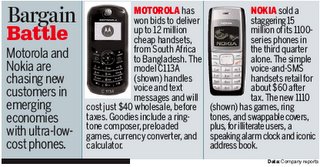

Mobile companies may make the most money by going downscale When it comes to sexy mobile phones, the stars of the moment are multimedia wonders such as the new RAZR V3x handset from Motorola Inc. () and Nokia Corp.'s () top-of-the-line N-90 camera phone with Carl Zeiss optics. Yet for all the attention they grab, these pricey gizmos are a sliver of the 800 million unit-per-year mobile-phone business. Increasingly, the real action is at the unglamorous end of the scale, among bare-bones Nokia and Motorola models priced under $50. Sales of such phones, which often handle just voice and text messaging, could grow 100% annually for the next five years.

That's feeding an explosion of new mobile users worldwide, especially in developing countries. In the past year, for instance, South Africa's No. 1 operator, Vodacom, has expanded its customer base 35%, thanks in part to ultracheap phones. "We've pushed for years to get cheaper handsets," says managing director Shameel Joosub. Vodacom has placed an order for 700,000 units of a new $30 Motorola model slated for 2006.

There are now about 2 billion mobile-phone users in the world, and market penetration is above 50% in advanced countries. But as prices for phones and service drop, another billion customers could sign up by 2010 from places such as China, India, Brazil, and Russia. "All the growth in subscribers is coming from emerging markets," says David Taylor, Motorola's director of strategy and operations for high-growth markets. Researchers predict that of the 1 billion cell phones expected to be sold in 2010, half will be in developing economies. Most will cost less than $40 -- still out of reach for the poorest one-third of the world's population but affordable for the middle third. "This market is wicked big," says senior analyst John Jackson of telecom researcher Yankee Group Research Inc. in Boston.

For now, the only serious contenders are Nokia and Motorola. The world's No. 1 and No. 2 makers, respectively, are scrambling to grab first-time buyers and build lifelong loyalty. "We want to bring new customers to our brand," says Antonio Torres, the director of business development and industry marketing for Nokia's entry business unit. Only Nokia and Motorola are able to churn out ultracheap phones with the features, quality, and brand names customers want. "This market is suited to mega-vendors with economies of scale," says senior analyst Neil Mawston with researcher Strategy Analytics near London. "Nokia and Motorola will own this segment."

Samsung Group, LG Electronics, and Sony Ericsson Mobile Communications haven't yet announced plans to sell sub-$50 handsets, preferring to rake in rich profits at the high end. That strategy could backfire, though, as the market shifts. "Samsung needs to do something because its share is not growing," says Carolina Milanesi, mobile analyst with researcher Gartner Inc. () near London.

PHONE SNOBS

Emerging low-cost Chinese makers have a different problem: Their volumes aren't high enough to match the efficiencies enjoyed by Nokia and Motorola, so they lose money on rock-bottom handsets. They're also not as adept at shrinking electronics and producing durable packages. Plus, status-conscious buyers in the third world turn up their noses at unknown marques. "Brazilians want brand names and are willing to pay a bit more for Nokia and Motorola," says Sérgio Pelegrino, director of GSM for Brasil Telecom.

Of course, moving downscale also poses risks for Nokia and Motorola. On Oct. 20, the Finnish giant reported that it sold 15 million entry-level 1100-series handsets in the third quarter alone. But despite an overall 29% jump in net profits, Wall Street was spooked by a 5.6% year-over-year decline in Nokia's average selling price, to $122.40, and drove its shares down 4.5%. Analyst Albert Lin with American Technology Research Inc. in San Francisco thinks investors are underestimating Nokia's ability to prosper in the low-price segment. "These phones can actually have higher margins than new high-end models," he says.

Already, both Nokia and Motorola are managing to produce handsets for as little as $25, allowing gross margins of 15% to 30% at current prices. That compares with overall 33% margins across Nokia's entire handset portfolio; Motorola's figures aren't disclosed. Big volumes of low-end phones also unleash scale economies that reduce production costs even for high-end models. "It's a key factor in getting our cost structure down," says Nokia's Torres. As sales shift to low-end phones, such savings should help Nokia maintain overall operating margins of 13.5% for years, forecasts analyst Richard Windsor of Nomura Securities in London. To seal the deal, Nokia is churning out technologies to slash the cost of building and operating wireless networks by a half. Bargain service boosts the impact of cheaper phones -- and should help the 4 billion people on earth who have never made a phone call.

By Andy Reinhardt in Paris, with Elizabeth Johnson in São Paulo, Brazil

NOVEMBER 7, 2005

EUROPEAN BUSINESS

When New Callers Opt For Old Handsets

Over the next five years, about 4 billion replacement handsets will be sold around the world. Billions of mobile-phone owners will retire their old devices for something new and cooler -- say, a 3G music/video phone. Their old phones will be thrown away, given to their kids, or tossed into a drawer. If historic patterns hold, only about 5%, or 200 million, will be returned to stores or secondhand dealers.

Still, that's a pretty big number. If every reused phone costs the mobile-phone industry a sale, the lost revenues could easily top $10 billion. That's why companies like Nokia Corp. () and Motorola Inc. () are hoping that ultralow-price models costing $30 to $40 at wholesale will give buyers reason to buy a new phone instead. "Why buy used when you could get a new phone with more features for the same price?" says equity analyst Albert Lin with American Technology Research in San Francisco.

Truth be told, nobody knows how big the used mobile market really is. A few years back, when the cheapest handsets cost $100, as many as 50% of all new mobile subscribers in Latin America used secondhand or gray-market phones, which are illegally imported to avoid taxes and customs duties, says researcher Yankee Group. Even now, operators in Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines say that 15% to 25% of new customers use secondhand phones. Market researcher Gartner figures the number could be 30% in India and 40% in Africa.

Still, there are reasons the secondhand business isn't far bigger. The main one: "Phones tend to die a natural death after four years, so there's a limit to the market," says Yankee Group analyst John Jackson. Batteries have an even shorter life, typically two years, and the cost of a new one can wipe out the profit margin for a reseller. Some phones are "locked" by operators and have to be hacked to be reused. And, of course, selling an old German phone in Tunisia means switching its software to Arabic. That, plus shipping, logistics, and sometimes smuggling, makes the economics pretty lousy. The mobile industry is also pressuring governments to lower duties to help stamp out the gray market.

Operators have mixed views of used phones. They help attract new subscribers who might not otherwise sign up. But a profusion of unknown devices on a mobile network can cause havoc and reduce performance. Worse, says Vodacom South Africa Managing Director Shameel Joosub, secondhand phones are less reliable and come with no warranties, so customer support calls from their owners can savage thin operator profit margins. "All things being equal, we'd rather put good new handsets into the hands of our customers," he says. Nokia and Motorola are hoping to do just that.

By Andy Reinhardt in Paris, with Assif Shameen in Singapore

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home